City of Kings at Howl!: Renewing the Faith of Graffiti

Written by J. Scott Orr

Photography by Daryl-Ann Saunders, Louise Gasparro, and Flint Gennari

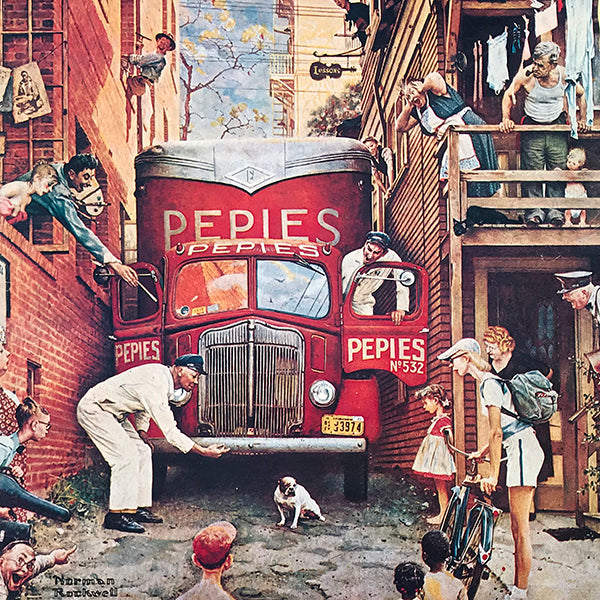

We call it street art, everything from the building-sized murals, to stenciled works, wheatpastes, even the stickers and chalk drawings that decorate the walls and sidewalks of urban passages around the globe. It’s about artists, sure, but today it’s also about appealing to curators and galleries and museums and the monied collectors who have put the bank in Banksy.

But in the beginning, back amid the hopelessness and desperation of a blighted and bankrupt early 70s New York City, it was called graffiti. It was daring and dangerous, its practitioners were a bunch of disenfranchised kids, there was no money involved, and it was really all about the name.

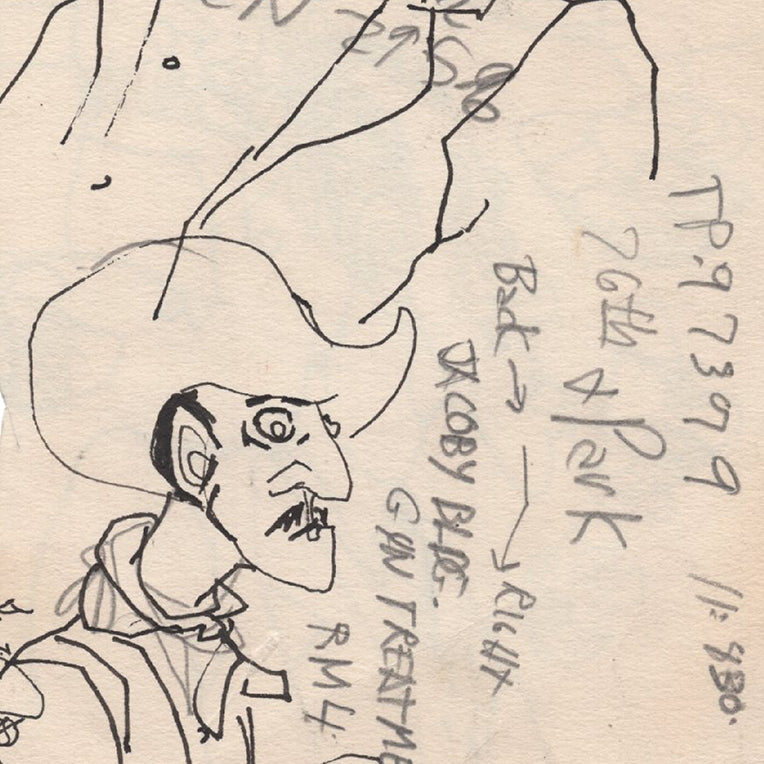

“What a quintessential marriage of cool and style to write your name in giant separate living letters, large as animals, lithe as snakes, mysterious as Arabic and Chinese curls of alphabet…No wonder the best graffiti writers…get the respect, call it glory, that they are known, famous and luminous as a rock star,” wrote author/journalist Norman Mailer in his seminal 1974 essay “The Faith of Graffiti.”

Now, with the help of renowned first-generation graffiti artist Al Diaz and a host of others, Howl! Happening is hoping to restore some of that respect and glory in a show called City of Kings. Presented in two parts, the exhibit opens at Howl! Happening, 6 E 1st St., on Nov. 19; followed by a second installation, Dec. 3, at Howl! Arts/Howl! Archive, 250 Bowery. It will feature contributions from artists and historians including CoCo 144, Taki 183, Crash, Lee Quiñones, Jay Edlin, filmmaker Charlie Ahearn, culture critic Carlo McCormick, artist and photographer Flint Gennari and Martha Cooper, the photographer whose work has come to define graffiti’s nascence.

“We want to show this evolution and how something that was created by a bunch of kids became absorbed into everyday pop culture.”

“We want to show this evolution and how something that was created by a bunch of kids became absorbed into everyday pop culture,” Diaz told UP Magazine in an interview. “It wasn’t really an art form in those early years. It was this kind of secret thing that kids were doing. Over time it got more and more complex as individual styles were created,” he said.

In addition to Diaz, the show is being curated by New Mexico Highlands University media arts and technology professor Mariah Fox Hausman and archivist and artist Eric ‘DEAL CIA’ Felisbret.

“The overarching goals of the City of Kings exhibition are to reveal the roles of New York and its inner-city youth as fundamental roots in the larger scope of what graffiti has become. We wanted the narrative to be told from that perspective, by the people who helped form it, rather than from outsiders looking in,” Fox Hausman said.

The exhibition will take viewers along a timeline from the very earliest days of graffiti through today.

The exhibition will take viewers along a timeline from the very earliest days of graffiti through today. It begins in the 1960s with tags by JULIO 204, who is widely acknowledged as the first to identify himself publicly by a name and street number. JULIO 204 was soon followed by a host of similarly identified graff writers, like CAY 161, Junior 161, CoCo 144, TAKI 183, Mike 171, SJK 171 and countless others. Diaz himself combined a name and number in his earliest tags, Bomb 1.

“In 1971, I had a cousin in Washington Heights and I went up there and I saw these tags, Snake 1, Stitch and those guys. I was 12 and I wanted to be cool like them. I was living on the Lower East Side and I brought it downtown,” Diaz said.

Soon Diaz’s tag, Bomb 1, could be found across the LES. But in bringing graffiti downtown, Diaz may have helped prod graffiti toward its next incarnation. Instead of simple names and numbers, Diaz pioneered a new art form that offered broader written messages through his partnership with Jean-Michel Basquiat in the graffiti collaboration SAMO©.

Similar breakthrough moments will be highlighted along the timeline at Howl! Happening. One such event was the creation of LEE Quinones’ Duck Wall, which was painted on a handball court and sparked an interest in moving graffiti beyond the subway system.

“At the time the graffiti community was strictly focused on painting subway trains—trains travel and have a larger audience. Walls don’t move so they were considered undesirable targets. Quinones was one of the most accomplished and artistic subway painters, so his high standing among his peers made the community reconsider walls as viable canvases,” said DEAL CIA.

Another moment came in 1988 when the brothers Sane and Smith painted their names on the side of the Brooklyn Bridge. This death-defying feat raised the location bar for subsequent generations of graffiti writers.

The exhibit also aims to clarify confusion over the difference between graffiti and the other forms of street art that followed. The emphasis on names is a big part of the distinction.

“We’re drawing a firm distinction between graffiti and street art.”

“We’re drawing a firm distinction between graffiti and street art because even though the terms are frequently used interchangeably the art forms are quite different,” said DEAL CIA.

“Graffiti and street art share many things in common but are clearly distinguished from each other by the fact that graffiti is primarily focused on names and letter structures. It is also a highly competitive art form almost like a sport. Through the majority of its history, it has been done illegally and it is a cultural expectation to do so,” he added.

In his 1974 essay, Mailer focused heavily on the illegal nature of graffiti, suggesting that the criminal component of the work gave it a unique sense of life-and-death urgency. “There was panic in the act, a species of writing with an eye over one’s shoulder for the oncoming of the authority,” he wrote.

“There was always art in a criminal act – no crime could ever be as automatic as a production process – but graffiti writers were somewhat opposite to criminals since they were living through the stages of the crime in order to commit an artistic act,” Mailer wrote.

Cooper, the photographer whose 1984 book Subway Art with colleague Henry Chalfant is considered to be the Bible of graffiti art and culture, also is contributing work to the exhibition. She noted that as a young photojournalist she was attracted to graffiti by its spontaneity, its decentralization and its organic evolution.

“One of the things that attracted me to graffiti was that they were doing it for themselves and there wasn’t any money in it.” – Martha Cooper.

“One of the things that attracted me to graffiti was that they were doing it for themselves and there wasn’t any money in it. So it was more of a pure art form in that sense,” she said in an interview.

One question the exhibit doesn’t address is what place graffiti, and the many forms of street art it has spawned, might assume in the broader timeline of art history. Does it have the historical significance of, say, impressionism in the 19th Century, or pop art in the 20th? That’s a question that might best be answered some decades hence.

“Graffiti qualifies as an art movement, as it includes specific visual forms, mediums, time periods, as well as an internal guiding philosophy practiced by its artists. Its visual inspiration can be found in mid-century and contemporary advertising, signage, packaging, typography, comic books and popular culture,” said Fox Hausman, the art historian.

“There is a strong presence all over the planet at this time,” added Diaz. “Some of it is really inspired, some isn’t. The fact that there are so many people involved in creating it and appreciating it certainly makes it a legitimate art form. Whether it’s a serious art movement or not, it’s something you cannot deny,” Diaz said.

No matter how history treats graffiti and its spawn, the movement will always have the distinction of being the first, and possibly the only, art form that was created by kids who had no goal other than to launch their names across Gotham via subway cars.

“The name is the faith of Graffiti.”

“The name,” early writer Cay 161 told Mailer, “is the faith of Graffiti.” The point was a profound one and CAY 161 apparently recognized this, because he said it twice during his interview with Mailer in the Washington Heights apartment of his parents. “The name is the faith,” he said.

J. Scott Orr is a career writer, editor and a recovering political journalist. He is publisher of the East Village art magazine B Scene Zine.