AL DIAZ: 4 THE CREATIVELY DEFIANT

Written by Kurt McVey

Editor’s Note:

Originally, the below profile on Lower East Side legend Al Diaz was slated for a December print release in UP’s Issue 4 – Politics. Like many publications, the ongoing pandemic has led to a series of shifting deadlines.

As the year comes to a close, we decided 4 the Creatively Defiant is best read in 2020, as we all await a new time.

***

It’s Sunday, September 27th in the exasperating year of “Oh Lord,” 2020, the all-too-revealing afternoon sun is just past its apex, and the artist Al Diaz is standing on the northeast corner of 6th Street and Avenue D in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. From a short distance away, “Al” more naturally than “Diaz,” a perennial, sinewy, capable 61, appears both patient and pensive, potential and kinetic, loitering with untold intention it would seem, but only to the uninitiated.

Al’s wearing his backpack and a custom t-shirt featuring one of his own colorful text-based anagrams. “Urban Guerilla” it says across the chest by way of a clever combination of exacted MTA train letters, u-turn symbols and red block letters pulled from WET PAINT subway signage. It’s as though Al, a true city-kid scion of Alphabet City, is offering up his own socio-political, Darwinian classification, but on his own terms and in his own apt language as we might say in the realms of art. Al, as many yet far too few know, helped set the stage for an artistic revolution in the ‘70s in the streets of Downtown New York City, a revolution that continues to ripple outward and expand like the universe itself. But you won’t catch Al’s face on an ironic novelty t-shirt in a fading Canal Street tourist trap. That highly fraught, ubiquitous territory of the masses belongs to great martyrs; to Che, to Biggie, to Lennon, to Andy, to Jean-Michel, to Jesus. A new face; heir apparent. George Floyd. The image. You know the one. The novel cultural apotheosis of twenty years and two millennia staring back at all of us.

Black canvas pro-keds sneakers with black shells laced up tightly are half-shrouded by a pair of baggy khaki cargo pants rolled up several times at the bottom in wide, thick folds. Behind Al looms the Jacob Riis Housing projects. A “testament to brutalism” as Al puts it. Grays and browns blend into a concrete soup which fills the mundane volume between endless right angles stretching two city super-blocks along the FDR, all the way up to 13th street.

“I could see the Empire State Building from the kitchen, which was kinda cool,” he says, throwing an index finger towards the famous skyscraper, which itself has now been gentrified and boxed in by a blight of nameless, characterless, architectural erections; spires of glass, steel and probably some kind of ‘space-age’ plastic or polymer; no soul, all ego and devoid.

“There was some turbulence for sure, but not constant noise and trouble,” says Al, a gifted storyteller of the written and oral traditions, and yet always cautious not to over-fetishize his own life, let alone his early years in the projects. “We lived on the sixth floor. When I was five, I was playing in the hall. The parents of this one family were always fighting. One day I overheard the mother shoot the father three times. She murdered him. I was five! I also saw a guy catch a stray bullet in the throat while walking out of the building. That was the early ‘70s.”

***

Al’s parents were Puerto Rican immigrants who landed in New York in 1955. By 56 they were married. By 57, Al’s older sister was born. Two years later, on June 10, 1959, Al arrived at Bellevue. A younger brother came later. “Dad was a hardworking, gentle kind of guy,” Al says in his own consistent, gentle manner. “He worked in sweatshops when I was a kid. Then in factories. You know, unskilled labor. Then he got a job as a driver. They were smart with their money. They worked really hard, bought a house, sold it, got a brownstone, bought property in Puerto Rico. They were upwardly mobile. But my mother was the engine; pushing, pushing, pushing.”

As a kid, Al remembers engaging in what he calls “proto-parkour” across the projects as well as various “delinquencies off the overpass.” He remembers Mayor John Lindsay and his big plans for urban renewal, which looked a lot like Ladybird Johnson cutting the grand opening ribbon in the Jacob Riis courtyard to much fanfare and photo-optimism. “Growing up here, we were regular kids; fistfights, falls, scrapes, playing and doing things that were incredibly dangerous. We used to run across the FDR. I saw a kid get decapitated once. By the mid ‘70s, though, it got bad, with drugs, gangs. The courtyard became a haven for these things. Maintenance was very low. We had incinerators. I remember the smell of burning garbage, metal cans filled with ashes. It was rough. It wasn’t ‘let’s move to the East Village.’ It was, ‘let’s get the hell out of here.’” In early 1975, they did. Al’s family moved to Brooklyn.

“Growing up here, we were regular kids; fistfights, falls, scrapes, playing and doing things that were incredibly dangerous. We used to run across the FDR. I saw a kid get decapitated once. By the mid ‘70s, though, it got bad, with drugs, gangs.”

Before starting west down 7th street, Al stops and nods to a residential building he remembers catching fire one unfortunate Christmas Eve; its residents, dozens of them, standing there helplessly on the frigid New York City streets in their underwear. “It’s not the type of thing you forget,” he says. Back then, as people like to say, 7th Street was incendiary in other ways. It was a gang block. “Kato’s Nunchuckers was a great gang name,” Al adds with a laugh. “There was The Dynamite Brothers. Once or twice I had to ask them for some help. There were lots of skulls and swastikas, but these guys didn’t even know what that stuff meant. It just looked mean. There’s Rose’s Candy Store, owned by an old Jewish family. These were tough-ass LES Jews. We would steal bubble gum and they would chase us.”

***

We move past a pizzeria that looks more entrenched than a dollar slice place. It’s nondescript, forgettable, but looks like it’s been around and unchanged for decades. “One time I’m in there on a nice summer day, getting a slice. A guy has Three-card Monte set up outside. The police show up and start pushing him into the car. Then I see the wife start pulling him out of the car, all within minutes. Then I hear, ‘leave him alone!’ Bottles start smashing in the street. More cops, more people. Turns into a full-scale riot. Hundreds of people on the streets. At this point I can’t even get out of the pizzeria. The fire department actually had to come break it up. Back then the cops had revolvers. I remember one of The Dynamite Brothers snatched a gun from a cop and passed it back like the bucket brigade. Both those guys are dead by the way.”

Al, a fighter, a survivor, a real cat, watched a lot of people in his universe pass away over the years; most recently, his father. “I’ve lost girlfriends, some close friends,” he says. “It’s not that I’m callous, but what happens is this; we’re certainly not here forever, so let’s make the best of it at this point. I’ve become very conscious of the fact that people die left and right.”

“It’s not that I’m callous, but what happens is this; we’re certainly not here forever, so let’s make the best of it at this point. I’ve become very conscious of the fact that people die left and right.”

Much of serious art-making is an active, defiant rebuke of death, a means to transcend mortality, as opposed to just boredom or invisibility. It’s equally redundant at this point to make the connection between cave drawings and street art, but in retracing Al’s steps, laid out over five decades, while seeing his neighborhood through his eyes and discussing all the extreme highs and lows of his life, one can’t help but pick up on a sort of timeless immortal hand, its enduring and ephemeral touch puncturing through temporal membranes as well as the countless, endlessly exuviated epidermal layers of this once and future city. This is Al’s territory, his caves and canyons, a place where blood has been spilt and spent, where his feet have pounded and tread a million times over, where he’s given chase and been chased. “I went to grammar school on the corner there,” he says. “Eight years of catholic school. I also lived here as an adult when I first got strung out. When you grow up in this neighborhood, everything is your stomping ground, all the buildings, apartments, shops… everything.”

To walk these streets with Al is to move beyond novelty and its even more grating but strangely endearing cousin, nostalgia, especially that over-cooked nostalgia for Downtown New York City in the early ‘80s, which has been beaten to death, reanimated, and beaten to a bloody cultural pulp over and over ad nauseam. We’ll never be there again, not exactly, but the writing is on the wall — the plywood boards, the grates, shutters, and empty stores. One of the unforeseen positive elements of the COVID-19 pandemic and the urban decay and desolation that continues to unfold, is the reality that it’s built something of a metaphysical wall between this generation and those aging SoHo bohemians, who are all quite cool, admittedly, perhaps even helped to define ‘cool,’ but need to boldly live and let live in the damn present.

Despite or perhaps because of Al’s rejection of this cultish leg-humping of the past, along with his quiet, mellow, ‘seen some shit’ humility, the man radiates a sort of organic authenticity. In a world of sedimentary fakery, social media and base reality virtue signaling, increased institutionalization (academia, media, cultural houses), corporate consolidation, PR posturing and brand prostitution, even among street artists, true authenticity is rarer than ever. Al’s entire career, it seems, can be viewed as an effort to cut through the charade-like machinations of Western civilization. This year-long, massive stripping away of society’s rubber fat-suit of performative silliness, is nothing short of an epic vindication of cats like Al.

***

We walk over an annoyingly ubiquitous piece of graffiti that says, “THE RiCH KiLLED NYC.” In late September, (as of this writing, it’s the second week of November) in the time of ‘Novel’ Corona, this seems only partially true. The uber-rich already treated New York like a spare walk-in closet in a ghost apartment that housed their Spring and Fall wardrobes, like a gargantuan international boutique that happened to have nice restaurants, music and theater venues, art galleries, museums and their endless fundraising galas. You know, culture. Once the brick and mortar institutions shuttered, whether fully or partially, or reopened with often angry, bitter, socially-distanced, but understandable masked-up sterility mandates, one realized quite quickly that New York and what it represents, what it is, has everything to do with the people who fill it with passion, life-blood, and soul magic and little to do with the institutional husks everyone was previously fighting each other to get into. Those usurpers and sycophants who abandoned and discarded New York like leftover takeout likely discard most things in their lives just as flippantly. Many creatives or even basic ham & eggers who relied and still rely on institutional validation to buoy their art and identities are now lost at sea, out to indefinite lunch, or back in the stale comforts of the parental womb, and good for them. “I don’t do the more obvious political stuff,” Al says, looking back down at the aforementioned tag. “It’s funny, the most fervent people who cry out, “New York is dead!” weren’t born here. Dude, you got here when you were 20! It’s all pedestrian, too obvious. You gotta move on too. Ok, they [the rich] did that. What else do we have to talk about?”

Once the brick and mortar institutions shuttered, whether fully or partially, or reopened with often angry, bitter, socially-distanced, but understandable masked-up sterility mandates, one realized quite quickly that New York and what it represents, what it is, has everything to do with the people who fill it with passion, life-blood, and soul magic and little to do with the institutional husks everyone was previously fighting each other to get into.

We pass by the old neighborhood laundromat on 7th, which used to be a not-so-secret front for a massive drug operation, heroin especially. It was the same with “The Lot,” directly across the street from Al’s grade school, St. Brigid’s, which he attended from 1st through 8th grade. Al explains that in the ‘80s and ‘90s, people would literally line up around the block to score. At 14, Al exited school, walked directly into “The Lot” across the street, and bought LSD.

Nearing Tompkins Square Park, on one of those NYC garbage cans that function like a USPS mailbox, we spy a weathered poster for something that says “Downtown 18,” an obvious inversion and clear play on Downtown 81, a dramatization-type film and “urban fairy tale” directed by Edo Bertoglio, written and produced by Glenn O’Brien and the photographer, Maripol. It stars a young Jean-Michel Basquiat meandering around the city and getting into misadventures. Al’s eyes don’t exactly roll as much as they sigh. “It’s just sort of blind romanticism,” he says. “To be clear, Downtown 81 is a pretty shitty film. I don’t mean to diss Maripol, but it’s kind of a shitty film. It’s not even Jean-Michel’s real voice. They have some shitty overdub. But because it’s Basquiat… I mean, the guy could wipe his ass… No, it’s not good. Not everything that Basquiat did was genius. There’s some really bad stuff too.”

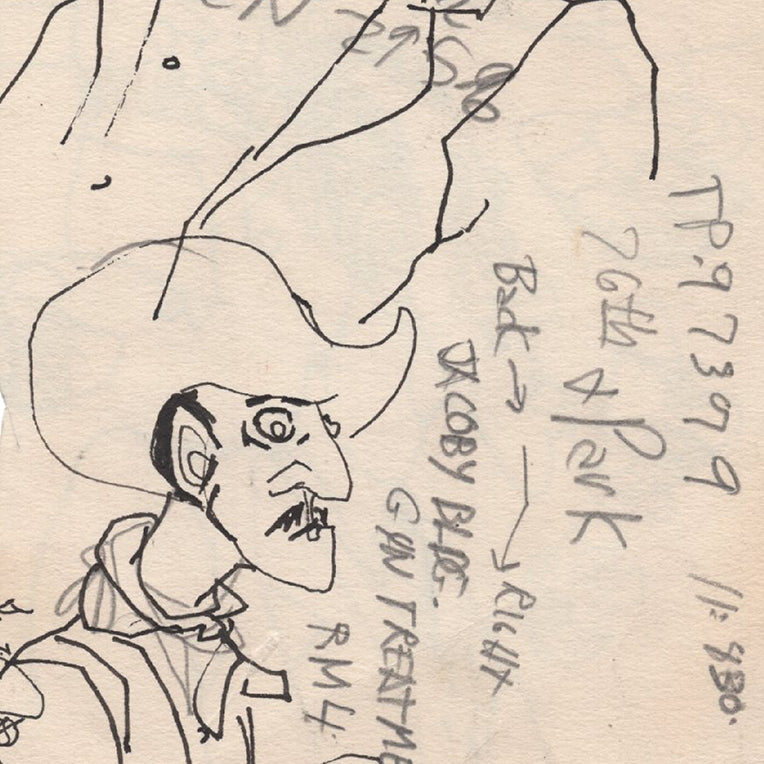

Now for the brief, requisite art canon mansplain about Al Diaz and Jean-Michel Basquiat. The wily pair met as teenagers at the alternative high school City-As-School (CAS) in Brooklyn Heights and together created the anonymous, joint graffiti moniker, SAMO©… which was something of a preternaturally sophisticated inside joke having to do with the hypocrisies, rote cycles and general “bogusness” of society, including but not limited to religion, cults, fashion, race, class, art, and to a less sophisticated degree, the pitfalls and ironic benefits of the “same old” crappy weed. Much of this narrative has been discussed elsewhere and quite extensively, not least of all in The Village Voice, where a December 11th, 1978 exclusive interview by Philip Faflick with “two sharp, personable teenagers named Jean (17) and Al (19),” all but ended their street anonymity and to some degree, their partnership as “magic marker Jeremiahs.” That article provides this random sampling of SAMO©… aphorisms:

SAMO© AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO GOD, STAR-TREK, AND RED DYE NO. 2.

SAMO© AS AN END TO MINDWASH RELIGION, NOWHERE POLITICS, AND BOGUS PHILOSOPHY

SAMO© AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO JOE NORMAL BOOSH-WAH-ZEE FANTASIES

SAMO© SAVES IDIOTS

SAMO© CAN SAVE THE AVERAGE JOE

SAMO© AS A NEW WAVE NEO ARTFORM

SAMO© AS AN ESCAPE CLAUSE

SAMO©…JUST IN CASE

Al claims he was the one who inspired and compelled Basquiat to bring his swag as an artist and poet to the streets, and this seems legit. SAMO©… began as a series of hand-drawn pamphlets and comic book hand-outs, given out both on the street, in school, and in small performance pieces uptown. But Al had already been doing work in the concrete wilds of NYC as a graffiti artist. Faflick pulled this out of a 19-year-old Albert Diaz in his Voice interview: “Oh man, graffiti? Forget it. I was right in there with Snake 1, Phase 2, and all those cats. ’Cause that was my life at that point. Bomb 1, that was me. I must have gone through a hundred different markers before I was 16. Then after that I hung it up.”

The first ever tag from the SAMO©… duo was on the corner of Church and Franklin. It read, SAMO© IS NOW! Presumably, Jean-Michel was hooked, claiming he would hit the streets thirty times a day on a good day. But by early 1980, Basquiat, now off on his own, was writing “SAMO IS DEAD” all over downtown and was beginning to cozy up to young artists like SVA-boys, Keith Haring and Kenny Scharf, as well as other Club 57 misfits, while Al leaned hard into music, featuring in bands like Liquid Liquid, Konk and Elephant Dance. “SAMO was 78-79,” notes Al in front of the lionized St. Marks hangout. “Club 57 was right after it, and me and Jean weren’t hanging out much anymore. They were still outsiders in a sense — Keith, Jean and Kenny — because this was my neighborhood. I was hanging with them, but there was always this separation because I felt rooted here, and everyone was from another place.”

The first ever tag from the SAMO©… duo was on the corner of Church and Franklin. It read, SAMO© IS NOW!

The details of Basquiat’s swift ascension and eventual, lamentable self-destruction have similarly been explored in detail elsewhere and beating a dead horse isn’t my bag baby. But perhaps a moment to interrogate the nature of transferable grief. Basquiat was found dead in his studio on Great Jones Street on August 12, 1988 by way of drug overdose. The death of Andy Warhol in 1987, it’s been speculated, helped push Jean-Michel into a depressive, alienated state. Soon after Basquiat was found, Al found himself falling deeper into a rabbit hole of hard drugs and hard living that would haunt him until he got fully clean in 2011.

“I was a carpenter most of my life,” Al says. “That’s how I made my living. I had a friend. Besides being a contractor, he was a big cocaine dealer. We would party regularly, and it became habitual. After Basquiat died, I was reintroduced to heroin. This time around, I kind of liked it. I started building a bar on Crosby Street. Our boss was feeding us heroin every day to get this project done. You could work for long hours on heroin. It’s like Viagra in the beginning but do it for three years and you don’t care about sex for the rest of your life. Suddenly I was there, like, ‘Oh man, I need to get high.’ It’s the highest anxiety you’ll ever feel. ‘Oh Christ, this has fucking got me!’ I started to roll with that, but then it took me 19 years in and out of detoxes and rehabs. I went to ten, 28-day programs, three long-term programs, various therapeutic communities and 36 medical detoxes. I was using the Medicaid card like it was an AmEx Gold Card. It was endless. I found myself in Rikers three times with a dope habit.”

“I was using the Medicaid card like it was an AmEx Gold Card. It was endless. I found myself in Rikers three times with a dope habit.”

In 2010, right after the film The Radiant Child, a Basquiat documentary by Tamra Davis, had come out, Al watched himself in the film — pale, withdrawn, cynical — and had a stark revelation, a literal, cinematic out of body experience. “After that, people wanted to talk to me and approach me,” Al recalls. “I felt like I had something to offer. I thought maybe there was some hope. I thanked Tamra Davis. She helped me get my life back. I saw myself and I was like, ‘I don’t’ want to be this guy, this disaster.’ I had lost my entire ‘40s after a relapse. I got sick of myself. So I changed the scenario.”

“I saw myself and I was like, ‘I don’t’ want to be this guy, this disaster.’ I had lost my entire ‘40s after a relapse. I got sick of myself. So I changed the scenario.”

***

Al brings me to a cafe in the East Village that boasts one of his recent, large-scale anagram murals on the building’s facade. It reads, “If We Remain Standing Still We Die In Place,” a phrase that’s become something of a life-mantra for Al. The work terminates with a black and white wheatpasted image (a woman in a dress wearing what looks like a WW1 gas mask) by street artist Jilly Ballistic. “When I met her, I was just doing the WET PAINT anagrams,” says Al. “I knew I needed more letters to comment on what she was doing, so I brought in the subway letters and numbers. It was time to grow.” Al calls these images at the end of his text crawls “captions.” Al was introduced to Jilly Ballistic by the filmmaker Nadia Szoid at one of her screenings. The location for the piece was arranged and curated by SacSix, who Al calls “one of the best wheatpaste artists and a hub in the community.”

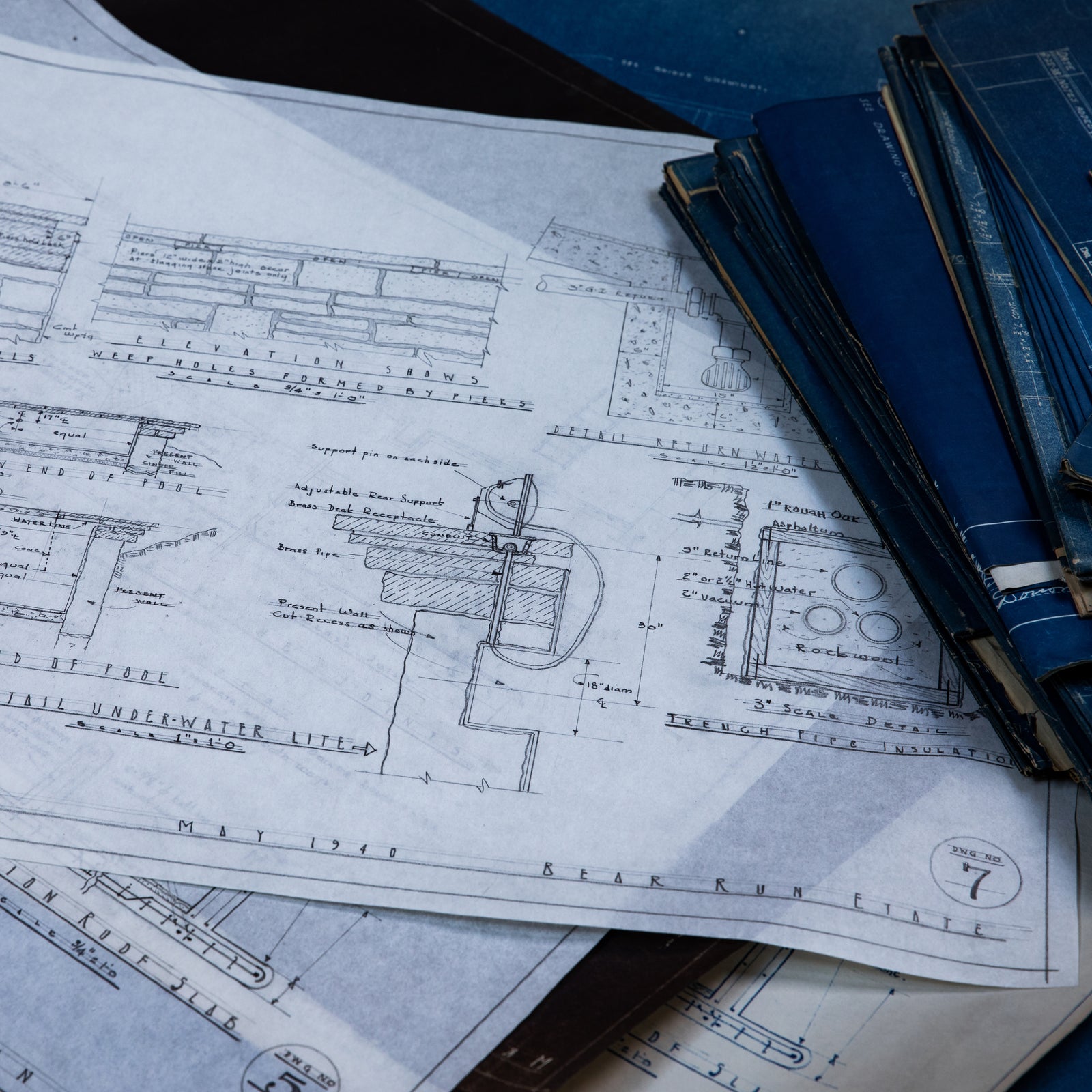

We soon find ourselves standing in front of Al’s Great Jones Street mural, now ripped and partially covered up, weathered and bombed with all the tags, stickers, painterly barnacles, flyers and other street detritus that two years invites, whether happily or not. Al executed this mural on the 30th anniversary of Basquiat’s death in 2018 with the curatorial help of his friend Adrian Wilson. That same sunny, Sunday morning on August 12, I received a surprise phone call by the artist Danny Minnick around 8am, compelling me to get my ass to 57 Great Jones to witness something special. When I arrived, he and Al were prepping the wall, hanging with Adrian and Curt Hoppe, and in good spirits. They were both highly present, joyous, roasting each other and busting balls like brothers do. On a billboard on the roof across the street, a mopey Basquiat doppelgänger was pushing pretentious bottled water. The text on Al’s mural, beside a full-scale, Richard Hambleton-style shadow-man silhouette of Jean-Michel reads: “I Didn’t Sign Up 2 Be Used As A Face 4 Selling Brand Named Crap.” After the mural was completed that afternoon, Al headed to Greenwood Cemetery to visit Jean-Michel’s grave, as he’s done every year since he passed. This time, however, Al was really able to let go.

***

Minnick had met Al the previous year at the Barbican in London for the 2017 Basquiat exhibition, Boom For Real. “Danny came up to me, [doing a solid Minnick impression] ‘Hey Al Diaz!’ He’s wearing all this GUCCI shit, but his pants are covered in paint. He starts talking. His voice doesn’t match his outfit. I got a kick out of it. We went to his studio. I’m like, ‘Who is this dude?’ I see a photo of him and Joni Mitchell. I’m like ‘What the hell?’” Minnick, a former professional skateboarder, actor, and now successful painter, street and mixed-media artist, seemed to seamlessly fill in long-vacant space in Al’s quietly tumultuous energy-galaxy. “I had recently moved to an apartment. I let him crash at my studio and paint while he was getting set up in NY. We became friends. Danny’s younger than me. He’s always an injection of energy.”

Minnick just so happened to be in New York during our walking tour and interview. We met up with him on the way to Al’s impressive solo exhibition, PREPARE 4 TURBULENCE, which ran from September 24th – October 3th, 2020, at One Art Space in Tribeca. Minnick was sitting outside a restaurant in SoHo, wearing a Bitches Brew T-shirt, that classic 1970 Miles Davis album with visionary cover art by the French-German painter, Mati Klarwein. “I was listening to Bitches Brew long before you were even born!” Al shouts just before we reach the table.

“That’s why you should have a shirt!” Minnick retorts, before sharing some kind words about Al. “He inspired me to keep working, to keep grinding. I learned a lot of techniques from Al, especially line control. Now it’s like an addiction. It’s like a beat. I’m a machine now.”

We pass what Al calls a “street tattoo” (black resin poured into carved concrete) at the doorway to what is now a hair salon on Crosby. To Al, it’s the bar that never came to fruition, ONYX, the place where he got hooked on heroin all those years ago. The women inside who cross over this emblem daily and with no context stare back at us, confused. We move down Leonard Street, where Al shares stories about the children of creatives who would throw amazing house parties, courtesy again of Basquiat’s strange pull with older female patrons.

There’s a different air about Al underground; more primal, hyper-observant, ageless, a little intimidating; poised to spring into action like some mid-sized concrete jungle cat eyeing its prey.

When we arrive at One Art Space, which only deserves a bad-rap for the pay-to-play model when the work isn’t good, Danny and I are struck again by the breath of medium, the quantity and quality (the craftsmanship, the consistency) of Al’s work, as well as the mature, poetic, alliterative urban-urbane messaging throughout, which never bludgeons the viewer, but reinforces the wise, deft, careful hand of a seasoned punk with nearly a half-century of dynamic artistic creation under his belt. Amongst the wood-panel pieces which spare no hypocrites, are a series of generational and source material-sampled mixed-media paintings which highlight Al’s strong grasp of composition and color theory; usually prime-adjacent colors caught somewhere between pastel and fluorescent; antidotes perhaps to those soupy childhood browns and grays. His ‘Alien Cubist’ assemblages; children of Rauschenberg, Kruger, and Kosuth. There’s the gorgeous, pseudo-religious street reliquaries which call back to Al’s Puerto Rican heritage flowering in the immediacy and intimacy of the urban landscape. Most impressive is a series of six large-scale canvas works, “a narrative in six panels,” each a different, vibrant base-color featuring Al’s now trademark anagrams, which express in cryptic chronological order the roller coaster ride that is the wild life of Al Diaz. “I was born in 59, a war-torn turbulent world, grew up during Vietnam and the ‘60s, witnessing murders, all the self-abuse…” Al pauses. “These were painful, difficult lessons. But there’s a bright ending. There’s hope, still hope.”

***

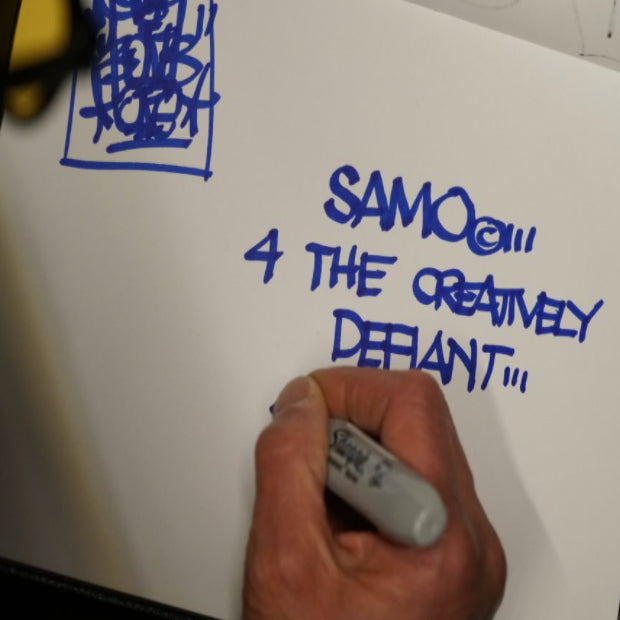

It’s Monday, October 26th just after 7pm, a misty, chilly night, and you follow Al Diaz down into the Canal Street subway station. You’ve just seen one of his latest, large-scale street murals featuring the words ‘WE AWAIT A NEW TIME.’ There’s a different air about Al underground; more primal, hyper-observant, ageless, a little intimidating; poised to spring into action like some mid-sized concrete jungle cat eyeing its prey. In this instance, it’s a shiny white subway wall, tiled and lit up by overhead fluorescent lighting and framed rather cinematically by two subway pillars. You keep a lookout and feel mounting exhilaration. Al pulls a black marker like it’s the long-lost Smith and Wesson The Dynamite Brothers jacked all those years ago from the cop. He pulls it like Johnny Ringo. Fast. Slick. And then you see it; the tag; a master at work. It flows out automatically with deep, instinctual confidence. He steps back and looks at his piece. The artist is alive and present. It reads: SAMO©… 4 THE CREATIVELY DEFIANT…