Jean-Michel Basquiat’s To Repel Ghosts is a nearly double-life-sized portrait of Basquiat’s friend and fellow artist, Jack Walls. The two had become fast friends after Robert Mapplethorpe introduced them in the West Village in the spring, and one evening while they were out together, Basquiat asked Walls to come by to paint his portrait. View To Repel Ghosts at Phillips New York until 15 November.

Brimming with the tactility and vigor that is characteristic of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s best work, To Repel Ghosts, 1985, exemplifies the central themes that preoccupied the artist at the apex of his career. The monumental work, measuring seven feet tall, is a nearly double-life-sized portrait of Basquiat’s friend and fellow artist, Jack Walls. Well known in 1980s downtown circles as Robert Mapplethorpe’s muse and romantic partner, Walls is rendered in Basquiat’s distinctive visual idiom—unmistakable by the gestural swathes of black, white, and yellow pigment—against a surface of affixed wooden boards.

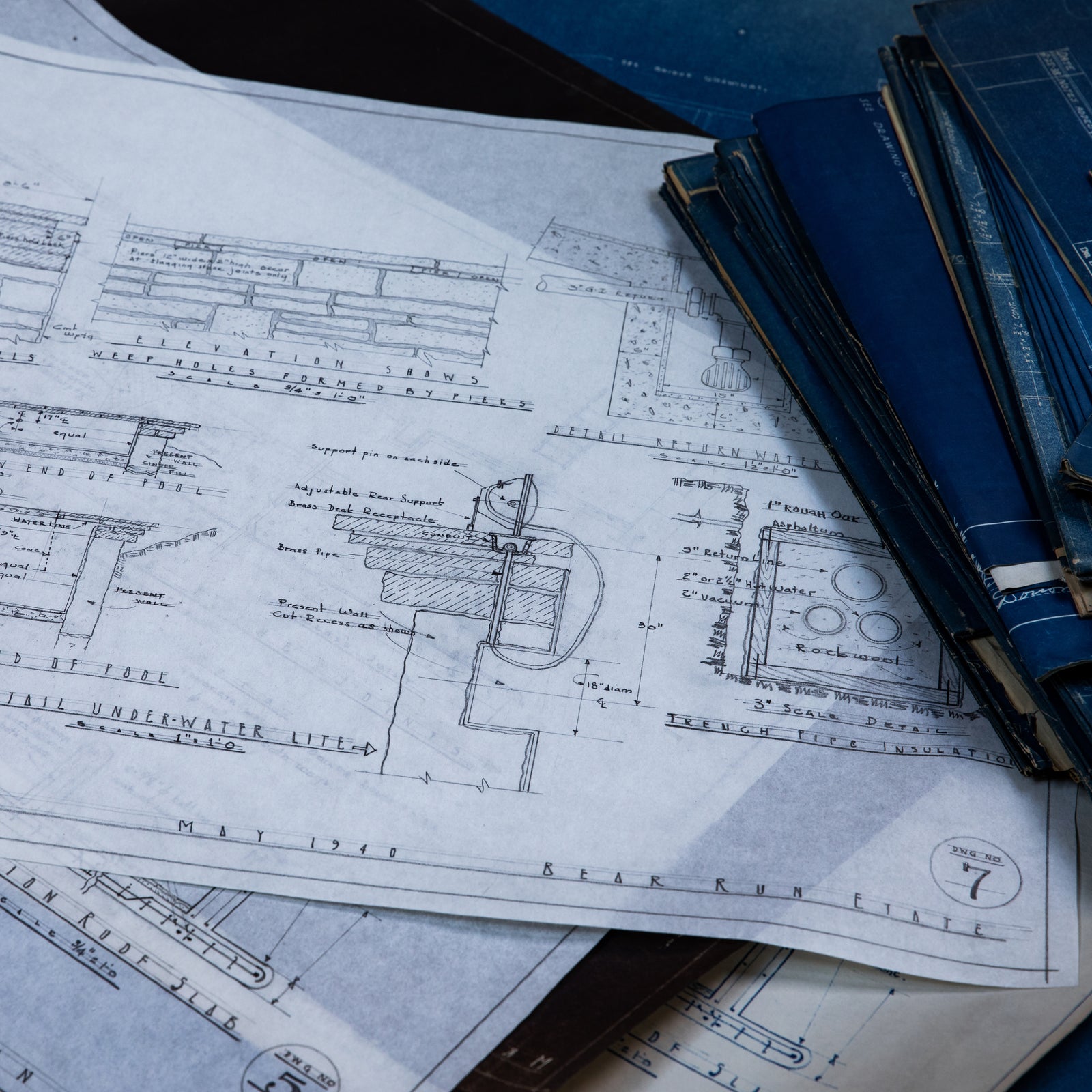

Basquiat’s penchant for incorporating doors and other found media into his practice first led him to experiment with timber slats for his 1984 masterwork Flexible, which employed the fencing that surrounded his Los Angeles studio. Exceedingly pleased with the resulting aesthetic effect, Basquiat soon returned to the idiosyncratic material, which he purchased from a Soho lumber yard to comprise the support of more than 17 paintings in the mid 1980s. Epitomizing his guiding principle to—quite literally—bring the urban environment into his studio, this major work from 1985 nods to Basquiat’s past as a street artist while anticipating the hallmarks of his mature style.

Sitting for a Painter

Recalling the ineffable experience of sitting for one of the greatest visionaries of the 20th century, Walls detailed the night in Basquiat’s legendary home and studio on Great Jones Street. The two had become fast friends after Mapplethorpe introduced them in the West Village in the spring, and one evening while they were out together, Basquiat asked Walls to come by to paint his portrait. A few days later, the two found themselves preparing to get to work on To Repel Ghosts while sheltering from a threatening blizzard outside. “It started out this way,” Walls remembered. “He asked me to remove my shoes and socks, standing with my bare foot propped up on one of his splinter laden wooden milk crates.” For a prop, Basquiat picked up a broomstick—“hold this,” he instructed—and placed it in his model’s hands.

“I remember Jean-Michel standing, paint brush in his right hand, left hand on his hip, in front of the tall vacant slats of wood assembled together in front of him, where the portrait he started to paint of me began to take shape with lightening quickness,” Walls reminisced. “There stood I, stick in my hands acting as muse. I watched Jean-Michel as he began to paint the double life sized portrait of me that night.” Though Walls was an experienced model for Mapplethorpe and other artists, he noticed he was uncharacteristically apprehensive that evening, at first posing a little uneasily. “Nervously? Yes. I was intimidated by Jean-Michel’s voodoo. Most downtown artists were awed by him in those days. He was a star even then… Not even a star, but a comet. The radiant child.”i

An Artist on the Rise

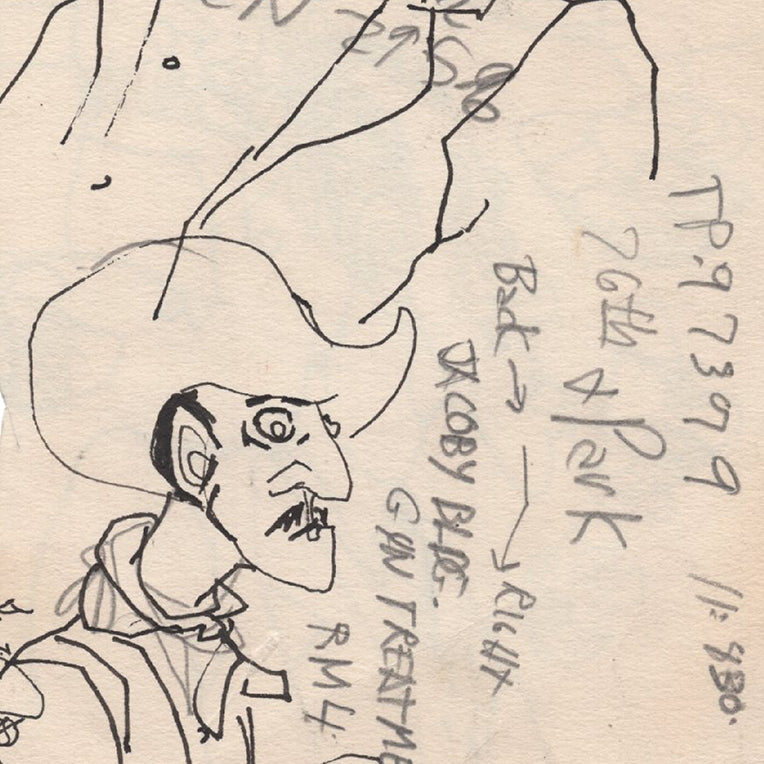

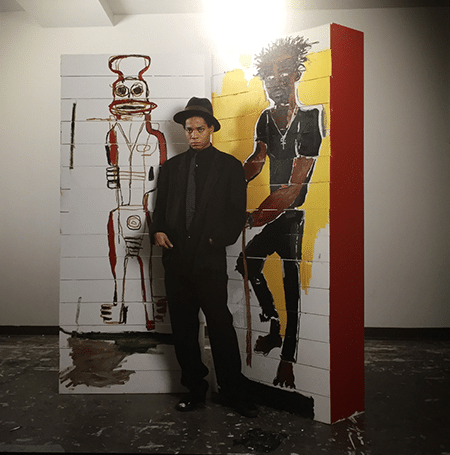

Indeed, To Repel Ghosts was executed at the height of Basquiat’s fame: firmly established as downtown New York’s resident superstar, his friendly rapport with Andy Warhol—already regarded as the indisputable icon of American post-war art—had evolved into a deeply collaborative professional relationship. Basquiat’s status as a fully-fledged art world celebrity was cemented by a cover story in The New York Times Magazine published soon after the execution of the present work. Detailing his meteoric rise to international recognition, the article painted a portrait of him as a young but prodigiously talented maverick. Standing triumphantly in a sharp suit and fedora, he meets the camera’s gaze while flanked by two paintings in his studio that showcase his singular practice—one of which was the then-unfinished To Repel Ghosts.

To Repel Ghosts

"The work of Jean-Michel Basquiat opens up opportunities to experience paintings and drawings in a new dimension. The overwhelming collection of references that we find on these surfaces—across geographies, chronologies, and histories—forces us to move differently as art historians."

—Jordana Saggese

Its title a gesture to colonialist understandings of voodoo practices, To Repel Ghosts reflects Basquiat’s engagement with his Afro-Caribbean heritage in the wake of his overnight success within a predominantly white art world. The artist began incorporating the expression into a handful of his works after his dealer Bruno Bischofberger introduced him to a Swiss ambassador who had lived across Africa for many years, Claudio Caratsch. Bischofberger recalled that one night when the two were at Caratsch’s house, the diplomat told Basquiat, “You know, in Africa art is made in a different way. Here it is art for art’s sake, and in Africa art is only made in order to do something with it, ‘to repel ghosts,” for instance.” Already familiar with West African belief systems, Basquiat was “amused that the ambassador, a studied ethnographer, was telling him about things he already knew.”ii The conversation led Basquiat to identify an affinity between his position within the diaspora and occult readings of African sculpture, manifested by visual tropes which would resurface throughout the rest of his oeuvre.

To Repel Ghosts was executed just a couple months after Basquiat first met Robert Farris Thompson, whose seminal book Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (1983) propelled the artist’s preoccupation with the legacy of the continent’s visual culture. The scholar devoted an entire chapter of the text, which Basquiat left open in his studio, to Yoruba culture and religion and its impact on Caribbean voodoo and Santería—a subject that the artist felt an especially personal resonance with as the child of a Haitian father and Puerto Rican mother. Conspicuous evocations to the imagery discussed by Thompson are visible in To Repel Ghosts: specifically in the figure’s distinctive almond-shaped eyes and broomstick, which could be redolent of an Ogboni or Haitian staff. Represented wearing a cross necklace while clutching the pole, Walls is specifically reminiscent of Santería’s syncretism of Yoruba religious concepts and Catholicism.

In 1986, after Basquiat expressed an interest in exhibiting his work in Africa, Caratsch and Bischofberger helped him secure a show at the French Cultural Center in the Ivory Coast. Including To Repel Ghosts, the show was an important milestone in Basquiat’s career, symbolizing a postcolonial reunion of Africa and the diasporic tradition.

The artist began to utilize Xerox photocopies in his work extensively in 1983, an example of which is visible in the lower left quadrant of To Repel Ghosts. Echoing both Warhol’s penchant for seriality and Robert Rauschenberg’s revolutionary collaged surfaces, this form of color printing allowed Basquiat to mine the conceptual complexities at the fore of postmodern discourse. It also provided the opportunity to “recycle” ideas and motifs—specifically text—from previous paintings into new contexts. Resulting in a tactility comprised of layers of wood, oil stick, and paper, this technique embodied the spirit that had been central to Basquiat’s approach since his days as the street artist SAMO©. According to the art historian Richard Marshall, the incorporation of Xerox underscored “his impulse signature to combine a number of materials, elements, and subjects from made, found, constructed, and collaged artifacts [that] were elemental to his works… The result was an aesthetic microcosm of the physical and visual reality of contemporary existence.iii

"The Black person is the protagonist in most of my paintings."

—Jean-Michel Basquiat

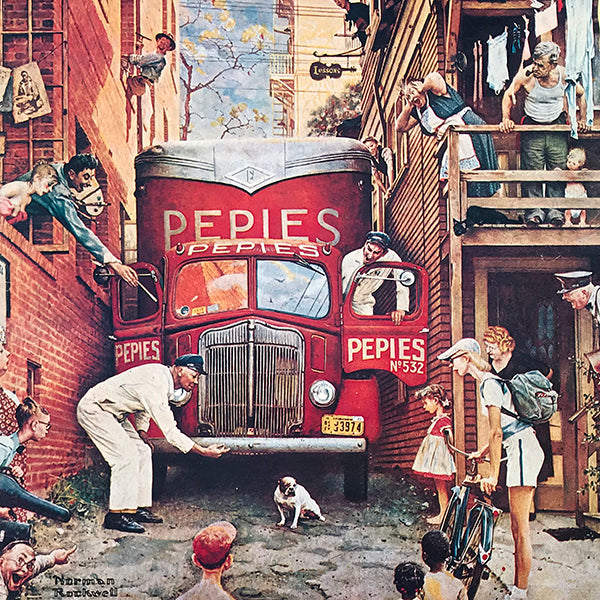

The drawing that Basquiat Xerox-ed for To Repel Ghosts was photocopied at least once more by the artist in 1985 to affix to a collaged wooden box. Though it is unclear why the amalgamation of enigmatic references so appealed to Basquiat, they provide an insightful look into the influences that propelled the artist’s all-too-brief career. The top of the sheet lists three chapters from Life on the Mississippi, the 1883 memoir of one of Basquiat’s favorite writers, Mark Twain; the center contains a series of names of jazz musicians, including saxophonist and “Young Billie” (most likely referring to Billie Holiday); the bottom half includes an inventory of animal species and mass-produced commodities, such a Pepsi and Camel cigarettes.

These references may contextualize him as in dialogue with both important historical figures and popular culture, but his revolutionary body of work had no predecessors. “Rather than directly influencing him,” Marshall pointed out, “Warhol and Rauschenberg, like other artists that Basquiat looked to, gave him a kind of art historical permission for his own endeavors.”iv Masterfully recapitulating the conceptual, material, and visual tenets that underpinned his corpus, To Repel Ghosts typifies the extraordinary vision that has earned Basquiat a vital role in the 20th century canon.